On this article, you’ll be taught sensible methods to transform uncooked textual content into numerical options that machine studying fashions can use, starting from statistical counts to semantic and contextual embeddings.

Subjects we are going to cowl embrace:

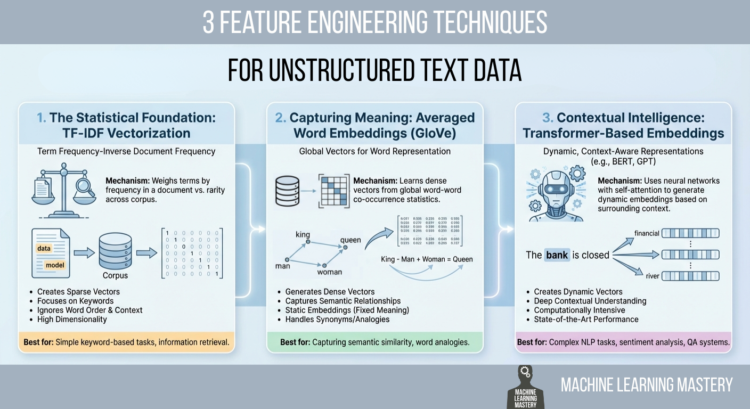

- Why TF-IDF stays a powerful statistical baseline and the right way to implement it.

- How averaged GloVe phrase embeddings seize that means past key phrases.

- How transformer-based embeddings present context-aware representations.

Let’s get proper into it.

3 Characteristic Engineering Strategies for Unstructured Textual content Information

Picture by Editor

Introduction

Machine studying fashions possess a elementary limitation that always frustrates newcomers to pure language processing (NLP): they can not learn. When you feed a uncooked e mail, a buyer evaluate, or a authorized contract right into a logistic regression or a neural community, the method will fail instantly. Algorithms are mathematical features that function on equations, they usually require numerical enter to operate. They don’t perceive phrases; they perceive vectors.

Characteristic engineering for textual content is a vital course of that bridges this hole. It’s the act of translating the qualitative nuances of human language into quantitative lists of numbers {that a} machine can course of. This translation layer is commonly the decisive think about a mannequin’s success. A classy algorithm fed with poorly engineered options will carry out worse than a easy algorithm fed with wealthy, consultant options.

The sector has undergone important evolution over the previous few a long time. It has advanced from easy counting mechanisms that deal with paperwork as luggage of unrelated phrases to advanced deep studying architectures that perceive the context of a phrase primarily based on its surrounding phrases.

This text covers three distinct approaches to this downside, starting from the statistical foundations of TF-IDF to the semantic averaging of GloVe vectors, and eventually to the state-of-the-art contextual embeddings offered by transformers.

1. The Statistical Basis: TF-IDF Vectorization

Essentially the most simple strategy to flip textual content into numbers is to rely them. This was the usual for many years. You possibly can merely rely the variety of instances a phrase seems in a doc, a way generally known as bag of phrases. Nevertheless, uncooked counts have a major flaw. In nearly any English textual content, essentially the most frequent phrases are grammatically needed however semantically empty articles and prepositions like “the,” “is,” “and,” or “of.” When you depend on uncooked counts, these widespread phrases will dominate your information, drowning out the uncommon, particular phrases that truly give the doc its that means.

To resolve this, we use time period frequency–inverse doc frequency (TF-IDF). This method weighs phrases not simply by how typically they seem in a selected doc, however by how uncommon they’re throughout your entire dataset. It’s a statistical balancing act designed to penalize widespread phrases and reward distinctive ones.

The primary half, time period frequency (TF), measures how continuously a time period happens in a doc. The second half, inverse doc frequency (IDF), measures the significance of a time period. The IDF rating is calculated by taking the logarithm of the overall variety of paperwork divided by the variety of paperwork that comprise the precise time period.

If the phrase “information” seems in each single doc in your dataset, its IDF rating approaches zero, successfully cancelling it out. Conversely, if the phrase “hallucination” seems in just one doc, its IDF rating could be very excessive. While you multiply TF by IDF, the result’s a characteristic vector that highlights precisely what makes a selected doc distinctive in comparison with the others.

Implementation and Code Rationalization

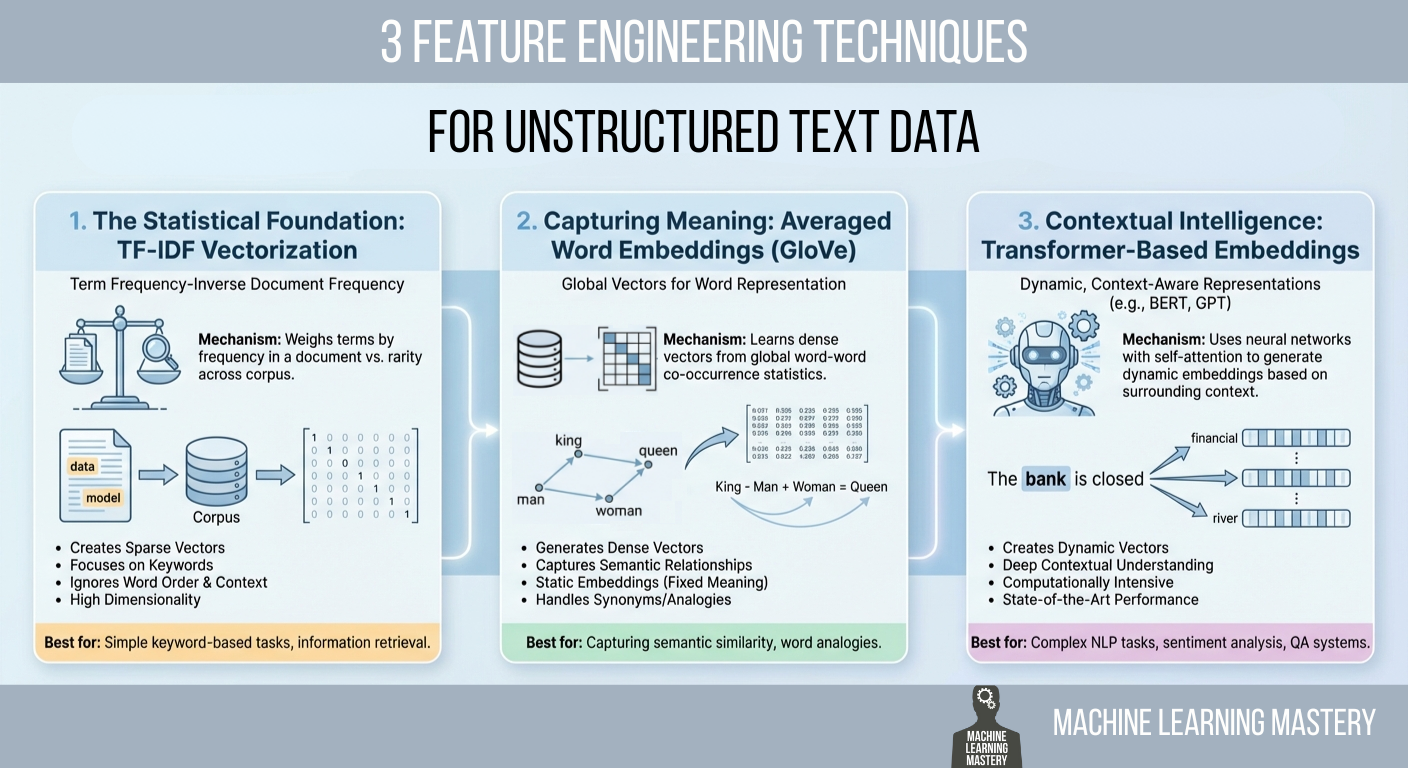

We are able to implement this effectively utilizing the scikit-learn TfidfVectorizer. On this instance, we take a small corpus of three sentences and convert them right into a matrix of numbers.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

from sklearn.feature_extraction.textual content import TfidfVectorizer import pandas as pd

# 1. Outline a small corpus of textual content paperwork = [ “The quick brown fox jumps.”, “The quick brown fox runs fast.”, “The slow brown dog sleeps.” ]

# 2. Initialize the Vectorizer # We restrict the options to the highest 100 phrases to maintain the vector dimension manageable vectorizer = TfidfVectorizer(max_features=100)

# 3. Match and Remodel the paperwork tfidf_matrix = vectorizer.fit_transform(paperwork)

# 4. View the outcome as a DataFrame for readability feature_names = vectorizer.get_feature_names_out() df_tfidf = pd.DataFrame(tfidf_matrix.toarray(), columns=feature_names)

print(df_tfidf) |

The code begins by importing the mandatory TfidfVectorizer class. We outline an inventory of strings that serves as our uncooked information. After we name fit_transform, the vectorizer first learns the vocabulary of your entire listing (the “match” step) after which transforms every doc right into a vector primarily based on that vocabulary.

The output is a Pandas DataFrame, the place every row represents a sentence, and every column represents a singular phrase discovered within the information.

2. Capturing Which means: Averaged Phrase Embeddings (GloVe)

Whereas TF-IDF is highly effective for key phrase matching, it suffers from an absence of semantic understanding. It treats the phrases “good” and “wonderful” as fully unrelated mathematical options as a result of they’ve completely different spellings. It doesn’t know that they imply almost the identical factor. To resolve this, we transfer to phrase embeddings.

Phrase embeddings are a way the place phrases are mapped to vectors of actual numbers. The core concept is that phrases with related meanings ought to have related mathematical representations. On this vector area, the space between the vector for “king” and “queen” is roughly much like the space between “man” and “girl.”

One of the vital common pre-trained embedding units is GloVe (world vectors for phrase illustration), developed by researchers at Stanford. You possibly can entry their analysis and datasets on the official Stanford GloVe mission web page. These vectors have been skilled on billions of phrases from Frequent Crawl and Wikipedia information. The mannequin seems to be at how typically phrases seem collectively (co-occurrence) to find out their semantic relationship.

To make use of this for characteristic engineering, we face a small hurdle. GloVe gives a vector for a single phrase, however our information often consists of sentences or paragraphs. A standard, efficient method to characterize a complete sentence is to calculate the imply of the vectors of the phrases it incorporates. When you’ve got a sentence with ten phrases, you search for the vector for every phrase and common them collectively. The result’s a single vector that represents the “common that means” of your entire sentence.

Implementation and Code Rationalization

For this instance, we are going to assume you might have downloaded a GloVe file (akin to glove.6B.50d.txt) from the Stanford hyperlink above. The code under hundreds these vectors into reminiscence and averages them for a pattern sentence.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 |

import numpy as np

# 1. Load the GloVe embeddings right into a dictionary # This assumes you might have the glove.6B.50d.txt file regionally embeddings_index = {} with open(‘glove.6B.50d.txt’, encoding=‘utf-8’) as f: for line in f: values = line.cut up() phrase = values[0] coefs = np.asarray(values[1:], dtype=‘float32’) embeddings_index[word] = coefs

print(f“Loaded {len(embeddings_index)} phrase vectors.”)

# 2. Outline a operate to vectorize a sentence def get_average_word2vec(tokens, vector_dict, generate_missing=False, ok=50): if len(tokens) < 1: return np.zeros(ok)

# Extract the vector for every phrase if it exists in our dictionary feature_vec = np.zeros((ok,), dtype=“float32”) rely = 0

for phrase in tokens: if phrase in vector_dict: feature_vec = np.add(feature_vec, vector_dict[word]) rely += 1

if rely == 0: return characteristic_vec

# Divide the sum by the rely to get the common feature_vec = np.divide(feature_vec, rely) return characteristic_vec

# 3. Apply to a brand new sentence sentence = “synthetic intelligence is fascinating”

# Easy tokenization by splitting on area tokens = sentence.decrease().cut up()

sentence_vector = get_average_word2vec(tokens, embeddings_index) print(f“The vector has a form of: {sentence_vector.form}”) print(sentence_vector[:5]) # Print first 5 numbers |

The code first builds a dictionary the place the keys are English phrases, and the values are the corresponding NumPy arrays representing their GloVe vectors. The operate get_average_word2vec iterates by means of the phrases in our enter sentence. It checks if the phrase exists in our GloVe dictionary; if it does, it provides that phrase’s vector to a working complete.

Lastly, it divides that complete sum by the variety of phrases discovered. This operation collapses the variable-length sentence right into a fixed-length vector (on this case, 50 dimensions). This numerical illustration captures the semantic subject of the sentence. A sentence about “canines” may have a mathematical common very near a sentence about “puppies,” even when they share no widespread phrases, which is a giant enchancment over TF-IDF.

3. Contextual Intelligence: Transformer-Primarily based Embeddings

The averaging technique described above represented a significant leap ahead, however it launched a brand new downside: it ignores order and context. While you common vectors, “The canine bit the person” and “The person bit the canine” lead to the very same vector as a result of they comprise the very same phrases. Moreover, the phrase “financial institution” has the identical static GloVe vector no matter whether or not you might be sitting on a “river financial institution” or visiting a “monetary financial institution.”

To resolve this, we use transformers, particularly fashions like BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers). Transformers don’t learn textual content sequentially from left to proper; they learn your entire sequence without delay utilizing a mechanism known as “self-attention.” This enables the mannequin to grasp that the that means of a phrase is outlined by the phrases round it.

After we use a transformer for characteristic engineering, we aren’t essentially coaching a mannequin from scratch. As a substitute, we use a pre-trained mannequin as a characteristic extractor. We feed our textual content into the mannequin, and we extract the output from the ultimate hidden layer. Particularly, fashions like BERT prepend a particular token to each sentence known as the [CLS] (classification) token. The vector illustration of this particular token after passing by means of the layers is designed to carry the mixture understanding of your entire sequence.

That is presently thought of a gold normal for textual content illustration. You possibly can learn the seminal paper relating to this structure, “Consideration Is All You Want,” or discover the documentation for the Hugging Face Transformers library, which has made these fashions accessible to Python builders.

Implementation and Code Rationalization

We’ll use the transformers library by Hugging Face and PyTorch to extract these options. Word that this technique is computationally heavier than the earlier two.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

from transformers import BertTokenizer, BertModel import torch

# 1. Initialize the Tokenizer and the Mannequin # We use ‘bert-base-uncased’, a smaller, environment friendly model of BERT tokenizer = BertTokenizer.from_pretrained(‘bert-base-uncased’) mannequin = BertModel.from_pretrained(‘bert-base-uncased’)

# 2. Preprocess the textual content textual content = “The financial institution of the river is muddy.” # return_tensors=”pt” tells it to return PyTorch tensors inputs = tokenizer(textual content, return_tensors=“pt”)

# 3. Move the enter by means of the mannequin # We use ‘no_grad()’ as a result of we’re solely extracting options, not coaching with torch.no_grad(): outputs = mannequin(**inputs)

# 4. Extract the options # ‘last_hidden_state’ incorporates vectors for all phrases # We often need the [CLS] token, which is at index 0 cls_embedding = outputs.last_hidden_state[:, 0, :]

print(f“Vector form: {cls_embedding.form}”) print(cls_embedding[0][:5]) |

On this block, we first load the BertTokenizer and BertModel. The tokenizer breaks the textual content into items that the mannequin acknowledges. We then go these tokens into the mannequin. The torch.no_grad() context supervisor is used right here to inform PyTorch that we don’t must calculate gradients, which saves reminiscence and computation since we’re solely doing inference (extraction), not coaching.

The outputs variable incorporates the activations from the final layer of the neural community. We slice this tensor to get [:, 0, :]. This particular slice targets the primary token of the sequence, the [CLS] token talked about earlier. This single vector (often 768 numbers lengthy for BERT Base) incorporates a deep, context-aware illustration of the sentence. Not like the GloVe common, this vector “is aware of” that the phrase “financial institution” on this sentence refers to a river as a result of it “paid consideration” to the phrases “river” and “muddy” throughout processing.

Conclusion

We now have traversed the panorama of textual content characteristic engineering from the easy to the delicate. We started with TF-IDF, a statistical technique that excels at key phrase matching and stays extremely efficient for easy doc retrieval or spam filtering. We moved to averaged phrase embeddings, akin to GloVe, which launched semantic that means and allowed fashions to grasp synonyms and analogies. Lastly, we examined transformer-based embeddings, which provide deep, context-aware representations that underpin essentially the most superior synthetic intelligence purposes at present.

There isn’t any single “finest” method amongst these three; there’s solely the suitable method in your constraints. TF-IDF is quick, interpretable, and requires no heavy {hardware}. Transformers present the best accuracy however require important computational energy and reminiscence. As a knowledge scientist or engineer, your function is to strike a stability between these trade-offs to construct the simplest answer in your particular downside.